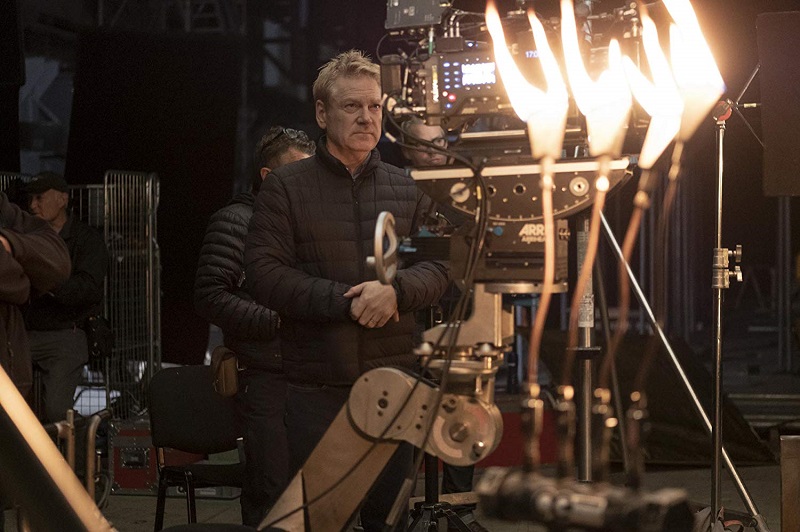

Ever wonder what William Shakespeare did once he decided to never put quill to paper? In the stunning All Is True, Kenneth Branagh directs and stars as The Bard in a part of the icon’s life that is not so well known. After his beloved The Globe Theatre burned to the ground, he moved back home to be by the side of his wife Anne Hathaway (Judi Dench), explore a relationship with his children which had been absent while he was in London as the toast of the town for two decades.

There are many facets of that premise that leads to a rich and layered look at one of history’s most recognizable figures and an aspect of his life journey that few know. Seriously, what would happen that would sudden cease the prose king from ever wielding his pen again? Branagh phoned The Movie Mensch for an exclusive chat where he gives us his thoughts about this time period of a man he knows as well as anyone. The star and director also salutes his fellow Oscar winner in Dame Dench and reveals how her uncanny experience performing Shakespeare in over 70 productions across mediums enhanced All Is True and elevated the explosive emotive core of this Shakespearian cinematic journey.

Branagh also lets us in on the filming of his latest Disney effort, the upcoming Artemis Fowl (Cinderella and Thor are two of his other Mouse House contributions). He also shares his utter joy at returning to playing Agatha Christie’s legendary sleuth, Hercule Poirot in Death on the Nile after his stunning directing-starring effort in Murder on the Orient Express. “I look forward to donning the mustache once more,” he teased.

The Movie Mensch: I adore this film. When I read about the movie, I immediately wanted to see it. One, because of you, but also, I was riveted by this idea of getting a window into the world of Shakespeare that’s not highlighted—those post-writing years. Did you learn something that maybe surprised you, as you geared up for this film?

Kenneth Branagh: I think in trying to find our starting point, which was the facts of his life—like these scandals that are recorded in the public records. We know that John Lane really did stand up in Holy Trinity Church and accuse Susanna (Shakespeare) of adultery and of her having gonorrhea. The fact of the enormous scandal that would produce to the returning celebrity homecoming king, that surprised me. But it also surprised me that, I suppose, that Shakespeare was so concerned, for instance, to purchase a coat of arms and to be called “gentleman.” I was surprised by what that seemed to suggest about his sensitivity about his position … his father’s position. I think the impression we have in other material that has him really assert his financial independence, that he really wants to protect himself against this financial scandal that his father suffered. To have been mayor of Stratford and then really disgraced. I was also surprised by the volatility of that world, in which the Puritans were trying to take over the church. It was not a particularly safe or peaceful place to come back to. I was surprised by that and then really encouraged by Ben Elton’s screenplay providing in that setting a Shakespeare, very ruminative and reflective in a place that was not necessarily offering him a nice, simple retirement.

The Movie Mensch: Yes, to put it mildly. Now, Ben Elton, you’ve worked with him. How did you come to read his screenplay and how did All Is True of come to be?

Kenneth Branagh: We met in 1988 at a Shakespeare performance I was in, Much Ado About Nothing, and he saw it and we became friends. He was in my film of Much Ado About Nothing and then, years later, I got to be in his own situation-comedy series about Shakespeare, Upstart Crow. It was there that I said to him, “would you consider writing a drama about this man, and would you consider looking at the facts of his life when he returned to Stratford, such as we know them and then a chamber drama that focuses on his family life? Perhaps, [it] can center on particularly the question of the grief that he feels for his son Hamnet. And do you believe there is any kind of mystery of suspense that we can hang that, around that grief?”

The Movie Mensch: Have you frequently thought of, over the years, the idea of what Shakespeare did during those retirement years?

Kenneth Branagh: It actually came to me a little more powerfully. When I was in a production of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, with Judi Dench, and I played Leontes—a man who loses a son through his own folly. He accuses his wife, falsely, of infidelity. The consequences of this act produce a collapse in various people, including his son Mamillius, around about 11 years old, who dies. Leontes suffering was something I talked to Ben about and said, “it feels to me this is not only in this play, it’s in King John, it’s in the later plays that were written just before the period of his life we’re talking about.” The man seemed to be preoccupied by the loss of his own child, preoccupied by the separation of twins, Hamnet and Judy. Ben has twins, and so he understands the special sort of considerations around those. The experience of being in The Winter’s Tale drove me a lot into the focus that we place in our presentation of Shakespeare here.

The Movie Mensch: You mentioned Dame Judi Dench. She’s given the world so many gifts with Shakespeare’s priceless prose. Do you have a favorite, and two, how did you get her involved with this project?

Kenneth Branagh: She was absolutely first choice to play Anne Hathaway. We worked together now for over 35 years. I’ve seen her be in Shakespeare and played opposite of her in Shakespeare. She was a fantastic Volumnia, the mother to Coriolanus. I play Coriolanus and she was a terrifying, inspiring mother. She played Paulina in The Winter’s Tale. It was a fantastic performance of maybe, maybe the strongest female character in Shakespeare. It was seeing that that really made me feel, Ben saw it as well, that that character, who speaks truth to power, was someone upon we could base Anne Hathaway. Judi came to this project with a real sense of protection and passion for Anne Hathaway.

The Movie Mensch: She is a truly fascinating character.

Kenneth Branagh: This is a woman who did not read or write, but Ben was determined to give her voice to this film. That voice that could put to Shakespeare, the indignity of humiliation that he may have hoisted on her by having published the sonnets. This kind of empathy, this compassion for Anne Hathaway that we saw when she played Paulina in The Winter’s Tale was something we thought would be a marvelous quality to have as well as her deep, deep seeded insight and knowledge of Shakespeare himself. She’s done 70 seasons at Stratford. She knows every inch of those places, and those villages, and those houses. She was an absolutely integral part of the whole thing.

The Movie Mensch: Yes, a true gift to all of us. Why do you personally think that Mr. Shakespeare never wrote another word, in the theatrical realm, after the Globe burned down? That was something that really struck me about your film.

Kenneth Branagh: There he was, he’d been on a kind of odyssey. He married Anne Hathaway at 18, when she was 26, and then he leaves for London. There are some lost years, that we can’t account for, but then spends the best part of 20 years becoming the most prominent writer of the age—37 plays of his own, authored or co-authored, while he did acting, directing, producing, writing. [He] producing the plays of many, many contemporaries. The dealing with the plague. Dealing with fire. The dealing of being in or out of royal favor. And then this massive, symbolic and actual destruction of his place of work. It felt as though the traumatic power of that would have been significant and I think that he, to some extent, might legitimately have been creatively spent. I think when the Globe burned down, he took that as a sign to head back, to try to find peace or resolution or that happy ending that he couldn’t find in his plays, without using the cheat of magic in his own life.

The Movie Mensch: As a director, you’ve run the gamut, from your own Shakespeare related films to Thor, Frankenstein to a Jack Ryan movie. And of course, the last time we spoke, for Cinderella. Is it true that variety is the spice of life when it comes to directing?

Kenneth Branagh: Well, I’ve enjoyed it, enormously. I must say, I enjoy the difference in the scale. I think as an artist, I do enjoy the yin and yang of these things. Working on this scale, swift and small, very personal, indeed, was a tremendous compliment to the large logistical exercise of making a film for Disney, like Artemis Fowl, about an 11 year old criminal mastermind where there are two worlds to establish, a contemporary world and the world of the fairies. [It] reminded me a lot of what Thor required, but it’s a massive operation by contrast. Also thematically, it’s very different in terms of subject matter. I would go from one to the other, with real pleasure. Then now back to the world of Hercule Poirot and Death on the Nile and the very different kind of entertainment. For me, that variety is critical.

The Movie Mensch: One of my favorite literary characters is Agatha Christie’s sleuth. I just adored your performance of him. Is it a joy of yours, to kind of dive into that role?

Kenneth Branagh: It is, to be perfectly honest. I love his humanity. I love his humor, I love his absolute delight in being the 100% of who he is, which is singular. I love his sort of self-knowledge and his self-mockery. Agatha Christie, she loved his kindness. Seems funny, an author talking about one of their creations like that. But I think, to some extent, he took over for her and sometimes. She found herself frustrated by the way the public had taken Poirot to their hearts and slightly dominated her output. But I think, ultimately, she was extremely fond of him and he brought out the best in her, so for me, yes, it’s a beautiful and a fun place to be. I look forward to donning the mustache once more.