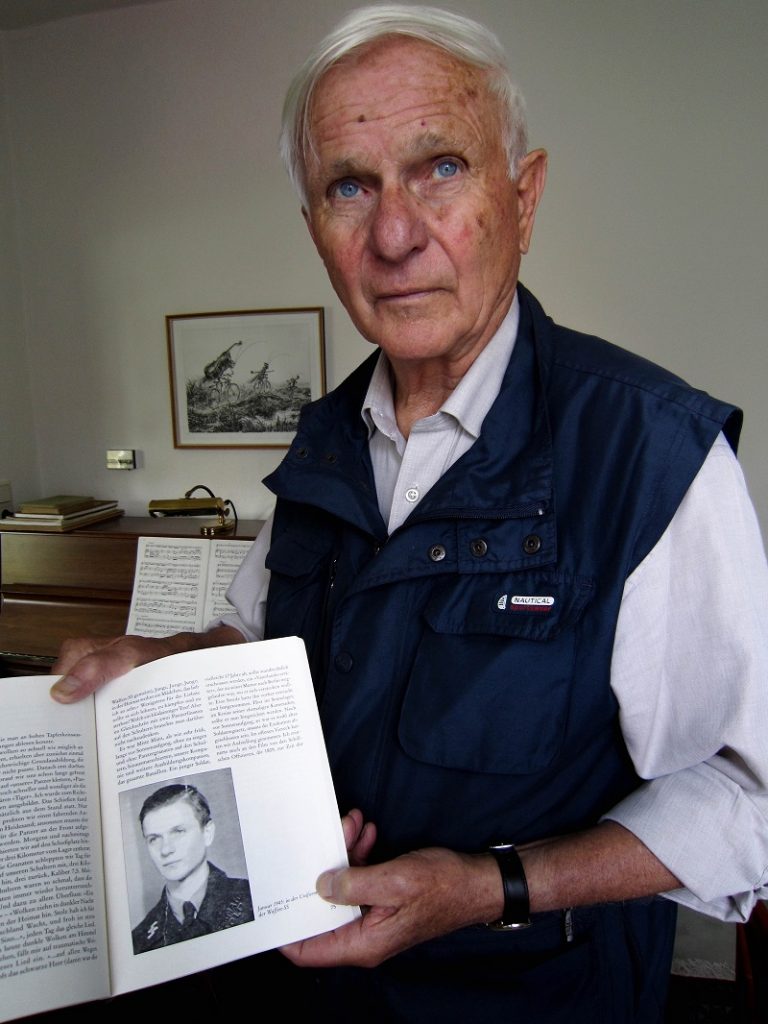

Director Luke Holland, in his big-screen documentary debut, has chosen the most emotionally epic of premises to center his feature. He filmed with supreme urgency. Time is running out on their lives. The last living generation of Hitler’s Third Reich, aka Hitler’s Youth, are on their final laps around the sun.

It’s equally as fascinating as it is heart-wrenching witnessing those who had a front-row seat to the dawn and demise of Nazism.

A common question asked of those in Germany after (and during) the war was, “what did you know about the elimination of the Jews from the continent?” What is painfully clear with Final Account, is that is exactly the purpose of this entire endeavor. The filmmaker asks pointed questions of these, essentially, brainwashed youth, in an attempt to wield answers to inquiries that have been posed for decades.

Many of the interviewees worked in the concentration camps but claim to not have known that millions of Jews were being executed and/or worked to death.

It is either denial, lying, or simple obliviousness. Whatever these subjects answer about those years, from roughly 1933-1945, varies greatly. It is a time of fondness for them. That could easily be explained as something any of us would feel reminiscing about our childhoods. The thing is, these folks’ youth was spent learning that Jews, Gypsies, Homosexuals, and others were not the ideal race and should not be trusted, and worse—put down by any means necessary. To many, these Hitler Youth experiences felt comparable to a summer camp, except with rampant racism, anti-Semitism, weapons training, and of course constant indoctrination. They even learned campfire songs that pitted Jews against the larger interest of the state of Germany.

These never-before-seen interviews will shock but also serve as a permanent record of what happened in Germany, what led up to fascism and an autocratic iron fist leadership that had no patience for anyone who wasn’t of pure blood. One can see the warning signs as if they were made of neon on a cloudy night.

Yet, these folks kept going on with their lives as if a raging storm were not coming their way. One man spoke of working at a labor camp and said that he just figured those who were wearing matching striped uniforms were political or war prisoners and never questioned it further. Hindsight is 20/20. But is it? The filmmaker seems to paint with a deep brush that what many of these interviewees are reporting is drowning in denial.

One who said he had a feeling what was occurring at the camps was not of the least bit humane. He spoke to the constant smell of burning flesh. He also noticed the trains that would bring legions of Jewish people and others to the concentration camps and how those who worked the camp, seemed to be gravely malnourished, and some, literally, were dying on the job. It’s a particularly fascinating interview as it shows two sides at work simultaneously in one individual. The mind cannot wrap itself around the idea that there would be a systematic elimination of an entire people. It is impossible to consider, he reports, and thus why he simply felt those there were prisoners of some sort and not targets for religious elimination.

One particular scene was especially moving. It took place at a nursing home and a group of four or five women was sitting around speaking about that era. Most claimed naïve innocence to the horrors of what their country was doing. But one particular woman became simultaneously enraged and inconsolably upset because she disagreed wholeheartedly. She felt everyone knew and everything else is simply a lie to make oneself feel better. To her, it was time to admit it before your time runs out and you have to answer to a higher power than a documentarian.

Near the end of the film, Holland caps his triumph of a cinematic experience by bringing in a batch of current youthful Germans to speak with one of the subjects. There is an unspoken rage at first that engulfs the room. The young people too find it impossible to believe that these people had no idea that there were mass murders happening all over Germany and Austria.

When the Hitler Youth alumni speak to it, the temperature in the room vastly elevates. One can see the war veteran getting emotional. That right there might explain the entire film in a nutshell. Deep down, this man knew about the killing and did nothing about it. Everything else he has said in the film and throughout his entire post-World War II life has seeped in denial.

It’s fascinating to see young Germans react as such. They almost resent that no one spoke up and tried to stop it. Even hearing that they too would be killed if they went against the societal grain. That sentiment doesn’t even phase the German youth. Wrong is wrong, no matter how scary.

Not to give those Hitler Youth any leeway in their awareness factor of the concentration camps, but perhaps the mind is so powerful that denial can embed itself so fervently in one’s psyche that it is as if the events witnessed never took place. The elderly man is shaken, practically to tears. It is as if he is coming to grips with a lifelong lie and suddenly and shockingly realizing that an entire generation of Germans simply went along with the worst of the human species’ horrors without giving it a second thought.

Grade: A+